|

| |

The Church in Urban Societies

How can the

church

not only

survive

but also thrive in the city? This is a critical question because cities are the centers that control the future of the people. If the church captures the cities for Christ, it will grow. If it loses the cities, it will become a movement on the margins of modern life.

The early church was an urban movement. It began in Jerusalem and spread through persecution to the cities of Samaria (Acts 8:5), Damascus (9:2), Caesarea (10:1), and Antioch (11:19).

Paul saw the importance of the city. His strategy was an urban strategy. He did not go to the many small villages in Asia Minor but to the cities; when he had planted churches in them, he declared his work finished in that region (Rom. 15:23).

The Reformation, too, was an urban movement. It began in the cities of northern Europe and captured the urban centers. From there it spread to the surrounding countryside. In the past the growth of Christianity was connected with cities. The Protestant church has since become largely a rural movement. This is due in part to the growth and adaptation of the church on the American frontier. It is also due to the fact that many Protestant missions focused their work on rural communities around the world.

Today, missions around the world are focusing on planting urban churches, but

too often they start peasant-style churches and, therefore, are unable to reach

city folk. Many church planters misunderstand and fear urban life. They succeed

best in the suburbs because these maintain some rural characteristics.

What has kept us from seeing, studying, and loving the city? Harvie Conn points out that Christians often have an anti-urban

bias. They see the city as a place of evil. Jacques Ellul (1970) expresses this fear in theological terms. He points out that the first city was built by Cain (Gen. 4:12) and that Babel was the city of corporate rebellion against God (Gen. 11 :1-9). Sodom, Gomorrah, and Babylon are symbols in the Bible of the concentration of evil in human hands.

Harvey Cox (1965) criticizes the anti-urban bias of the church. He sees the village as a place where people are bound by the tyranny of tradition and by Hinduism, Islam, and other religions. To him the city is a place where people are free to discover and believe the living God of the Bible.

Both views express certain truths and both are reductionistic. The city is indeed a place where sin abounds. Because it is the center of human activity and because humans are sinners, evil grows freely in urban settings. The moral checks of traditional societies on excessive evil are gone and people are free to sin openly. Furthermore, where there is power there is the potential, at least, for corruption and oppression. The hierarchical structure of the city, along with its generally impersonal nature, allows for the ill treatment of a great many people.

The city also is a place where God is mightily at work establishing his rule over human societies. An often quoted adage is that "the Bible begins in a garden and ends in a city." In the Old Testament, Jerusalem stands in contrast to Babylon and the cities of refuge to Sodom and Gomorrah. In the New Testament, Jesus was associated with the city. He was born in the "city of David" (Luke 2:11), preached in the city (Matt. 9:35), wept over the city (Luke 19:41), and was crucified and rose near a city (John 19:20). Paul, too was a city person. He was born in Tarsus (Acts 22:3), set out on his mission from Antioch (Acts 13), and used an urban strategy, planting churches in the main cities with the expectation that they would spread the gospel to neighboring towns and villages (Acts 16:11-40; 17:16-33; 18:1-11; 19:1-10; 28:16-31). The writer of Hebrews looks for a new city whose builder is God (Heb.11:10).

In early church history, Jerusalem, Antioch, Ephesus, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Rome became, successively, the centers from which the church reached out to the tribes of Europe, to the villages of South India, and to the towns of China.

The city is a place where the wheat and the tares both ripen to maturity. Above all, it is the place where the church must proclaim the message of God's salvation and his reign. We can be assured that God is already at work in both hidden and visible ways. But to take this stand, we must overcome our anti-urban bias and learn to understand and love the city and its people.

Planting Churches

Obviously no chapter, or book, can fully explore the issues involved in planting urban churches, given the diversity of cities. No single set of principles can be formulated. The methods for planting churches among the Baluch immigrants in Karachi must, of necessity, be radically different from the methods of planting churches among the urban elite in Rio de Janeiro or the suburbs of Chicago.

Another reason is that our understanding of church planting in urban settings is still so new and incomplete that any generalizations we make now will soon be revised.

Our purpose here is not to explore exhaustively the methods for planting churches in urban settings. Rather it is to make us aware of the need to study and understand the specific urban setting in which we minister and to be sensitive to the way the social and cultural contexts of people influence the ways in which they hear and believe the gospel.

Moreover, we must remember that the work of evangelism is the work of the Holy Spirit, who is already at work in the city. We need to train people who do not trust in their techniques and strate- gies as much as they do the leading and power of the Spirit.

The Church and Diversity

As we have seen, one of the hallmarks of the city is diversity. This raises a serious question: how should the church respond to these differences?

One of the great obstacles to effective Christian witness in the city is our own

preconceptions of what constitutes a church. We often believe that it must have

a seminary-trained pastor, a church building, hymns, offerings, and sermons

because these were characteristics of the rural and suburban churches in which many of us grew up. While some strong churches in cities do fit this pat- tern, most will not. Too often we are peasants seeking to plant rural churches in urban settings. We need to break from our stereotypes of the church if we want to be effective church planters in the city. One thing is clear. There will be no one form of church that serves as the model for all the others. There will be house churches, store-fronts, local congregations, and megachurches; ethnic churches and integrated churches; churches that stress high ritual order and those that emphasize informality. No one of them can serve the spiritual needs of all people. And each of them has its own temptations and faults.

One thing many urban congregations are learning is the need to incorporate diversity into the local church itself. Different worship services with different worship styles are often held in the same sanctuary at different times on Sunday morning, or they may be incorporated in the same service. Different ethnic groups may form congregations that work together and use the same facilities. In one North American case, three small churches, composed of whites, African-Americans, and Hispanics respectively, merged to form a single church so that they could afford a pastor.

Probably less understood is that many urban churches are made up not of one congregation but of several intersecting congregations. In rural churches, everyone is expected to attend all the church services and social pressure is put on members to do so. In urban churches, one group meets for the Sunday services but other groups, equally a part of the church and its ministries, may attend Bible studies, counseling sessions, and fellowship groups during the week. Each group should have a place and a say in the life of the church. In such settings there may be few ways to build a sense of common community. Rather, each group in the church needs to be nurtured and fed in its own gathering.

Finally, the church will take different shapes in different communities. Megachurches appeal largely to middle- and upper-class people seeking multiple ministries. They can be effective if they have multiple subcongregations and small groups to provide people with a place for fellowship and personal sharing. Store- fronts and missions reach out to the poor and street dwellers, small churches to those seeking intimacy and a strong sense of community, and cathedrals to those wanting ritual expressions of their faith.

Decision-making in the City

How do urban people make decisions? As we have seen, in tribal societies major decisions are made by families, kinship groups, and tribal leaders. In peasant societies decisions are made by families that belong to ethnic or class groups in the village. Here family networks often process a major decision together. In both cases the result is often group movements to Christ. But what

about the city?

'

We must avoid reducing decision-making in the city to a sin- gle stereotype. As in other areas of city life, we face here a bewildering diversity. In tribal and peasant enclaves in cities, group decisions still take place. People shop at family-owned stores where personal ties are important, and they discuss choices with their neighbors. Outside their neighborhood, however, they learn to make decisions as city folk do, and this fact begins to change their lives.

People in ghettos, bustees, favelas, shanty towns, and other enclaves of the poor have their own ways of making decisions. As Oscar Lewis shows (1961), economic decisions must be made on the basis of survival. Whoever gets some money must share it with others who have nothing because in the future he or she will be the one who needs help. Decisions are often made at the last moment. It is hard to make lasting commitments and long-range plans. Consequently relationships are of necessity fragile and the future uncertain.

Planting suburban-style churches in such contexts is almost impossible. Services must be based on last minute arrangements because those who promised to serve do not show up. Leadership often lies in the hands of a few unpaid persons who can inspire others to participate. Missionaries to these communities must be very flexible and not become upset when things do not work out the way they planned. They must be able to choose another course of action on the spur of the moment, something many from the west find hard to do. Charismatic churches have been successful in such communities, in part, because they are adhocracies rather than bureaucracies.

Middle- and upper-class urban people tend to make individual decisions based on reason and feelings. They ask the advice of knowledgeable friends and neighbors, the "opinion leaders" whose advice they trust in the matter at hand. They ask one friend about cameras, another about doctors, and a third about religion. In such settings, the gospel often spreads along networks of friends and associates.

Window Shopping the Gospel

One way truly urban people gain information to make decisions is by window

shopping. People in small towns go regularly to the same store and buy what the

shopkeeper recommends because they trust him or her. In large cities, shops have

large display windows where passing strangers look at the merchandise. They make their choices on the basis of price, quality, and appeal, rather than on personal trust in the merchant.

Window shopping is closely tied to the concept of "territory." Edward Hall

(1966) and others have argued that all people have a sense of territory-a sense

that different geographic and social space "belongs" to different people and

groups and is used for different functions. The concept of ownership is far broader than legal possession. People living together often feel that they own their neighborhoods even though the streets and parks belong to the general public.

City shops are semipublic. Strangers may enter to purchase goods but the space

"belongs" to the owners and salespeople are free to talk to the strangers about

buying goods and services. Consequently, to enter a store is a tentative commitment to buying something. People do not expect to go to a shop just to visit or to argue about religion.

Similarly, a church is a semipublic place and people who enter it generally have

some interest in Christianity. But they also realize they have entered territory owned by Christians. What about people who are only casually interested or curious? Where can they look at Christianity without being pressured to convert?

Neutral territory is public space not owned by any particular interest group. It is sidewalks and markets where people can look at commodities on display. It is public roads with their billboards and parades, and stadiums and public auditoriums where

one can

remain a spectator lost in the crowds. In all these places people can examine new ideas and products without a pressure to "buy." What implications does this have for evangelism in the city? One thing is clear: many city folk will not come to a church, even for evangelistic meetings. They see the church building as religious territory. To enter it is to make a first positive step to becoming a Christian, a step they are not ready to make. They may be willing to look at Christianity, but they will do so only in the safety of some neutral territory where no precommitment is needed. They just want to window shop the gospel.

What are some of these neutral territories that the church should explore in evangelistic outreach?

Streets, parks, stadiums, and auditoriums

Streets, parks, stadiums, and auditoriums-these are public spaces and although they are used for specific functions such as rock concerts or trade fairs, they are generally thought of as neutral

territory. The sheer size of large gatherings in them also guarantees a person's anonymity. Moreover, the fact that different types of functions are held at the same site prevents it from being identified closely with anyone of them. In North America, a stadium may host a football game one day, a music festival the next, and a gospel crusade the third.

The church in the city has long used empty lots, parks, and streets for public meetings. In many parts of the world, these are important places where films can be shown and the gospel preached. For example, the Christian and Missionary Alliance churches in Lima, Peru, have developed a cycle in which evangelistic meetings are held in tents near a church, then several weeks are given to incorporating new converts into the church, and then another set of evangelistic meetings follows.

More recently stadiums and civic auditoriums have become important places for

public rallies where people may come to window shop the gospel. For instance, the Eagles Communication Team in Singapore stages modern musical concerts in public auditoriums. Each concert is followed by an evangelistic challenge and appeal. The team regularly fills auditoriums with young people, many of them non-Christians.

In many cities congregations have bought theaters and converted them into churches, attracting people who would not enter the

door of a building that looks like a church. Others use shops for store-front churches and shopping malls for large meeting halls.

Restaurants and banquet halls

City folk eat out regularly. It should not surprise us, therefore, that churches are discovering that restaurants and hotels are good places for evangelism. For years the Christian Business Men's Fellowship and the Full Gospel Business Men's Fellowship in North America have used restaurants to make non-Christian business- men feel at home. Others are using them as meeting places for young adults and seekers' groups.

In Singapore the Eagles Communication Team ministers to upper-class professionals by organizing banquets in top-rated hotels. They encourage Christian doctors, lawyers, teachers, and business people to buy tickets and invite non-Christian friends as guests. The banquet is followed by a musical concert and a brief evangelistic presentation. Most of the guests would feel uncomfortable in a church, but at the hotel they can enjoy a meal together with their friends and look at Christianity without the pressure to convert.

Retreats, festivals, and pilgrimage centers

In recent decades, evangelicals have discovered the importance of camps and retreats, but the idea is not new. Throughout history the church has made extensive use of retreats, not only as places for spiritual formation but also for people to explore faith. Some in Asia are exploring the use of ashrams and other retreat centers where people, harried by urban life, can get away for times of reflection and decision.

In many cities of the world, religious festivals are celebrated in public with street parades and mass rallies. Christians in some of these cities are beginning to do so as well, making the public aware of the Good News.

Neutral Territory and Sacred Space

Neutral territory is public space where secular people can look at Christianity without being pressured to convert. It is a place of evangelism, similar in ways to the Court of the

Gentiles in the Jewish temple. But the church also needs "sacred" space where it gathers to worship and fellowship. Outsiders are welcome, but here the church reaffirms its identity as the body of Christ.

The form of the sacred place will vary. Some congregations seek to express the

greatness, mystery, and providence of God in all creation by building large

cathedrals. Others emphasize the presence of Christ and fellowship in the congregation and build churches. Still others symbolize the power of the Holy Spirit in the life of each believer by constructing chapels and informal auditoriums.

The forms also vary according to the social class, ethnic tastes, and culture of

people. What is common is a sacred place where the congregation as congregation

gathers regularly to meet God. Without sacred places and times to give

expression to our experiences with God, we are in danger of being drawn into the

secular world of the city and forgetting God's magnificent presence among us. Or we are in danger of becoming social clubs in which Christ is only a member.

There is another reason why the church needs sacred space. It is a testimony to the world of the presence of the church. Non- Christians may be unwilling to enter a church building, but its very existence reminds them of Christianity. In Seoul, Korea, the rapid proliferation of church buildings with crosses on them is seen by non-Christians and Christians alike as witness to the growth of the church. Muslims are aware of the importance of sacred symbols in the city and are investing great amounts of money in building impressive mosques in cities around the world. Likewise, many Christian communities around the world want church buildings that publicly symbolize their presence in the city.

The tension between neutral space and sacred space reflects the tension the church faces between being in a secular world and yet not of it. In the world it is a witness; apart it renews itself. If it lives only in neutral territory, it is in danger of losing sight of its Lord; if only in sacred territory, of becoming ingrown and old. The church needs to be present in both territories.

Ministry in Mobile Communities

As we have seen, urban people are mobile. They travel long distances each day. They move to find jobs and better lives, or are forced out of their squatter settlements by police. Many are part

of the flood of peasant and tribal immigrants that streams to the city to find a

new life. How can the church evangelize and minister to such people?

Ministry to Mobile People

City people are people on the move. Buses, cycles, rickshaws, trains, elevators, and cars are part of their daily lives. This mobility

changes the shape of the church in the city. Those in poor communities are less mobile and so retain a sense of the neighborhood parish. The church building is a place not only for worship but also for visiting and community activities. The members share in the needs and joys of each other's daily lives.

Churches in affluent parts of the city are often commuter congregations that draw together people, not on the basis of geography but of common interest. Unlike neighborhood parishes, these churches are often socially and culturally homogeneous and find it hard to reach out to people of another class or ethnic community.

Commuter churches need to work hard at building a true sense of Christian community in their congregations. This is difficult because commuting prevents their members from developing the multiplex relationships necessary for intimate fellowship. Many seek to build a sense of community by extending the range of church activities beyond worship and evangelism to informal gatherings, recreation, and even neighborhood projects. So long as members in a congregation see each other only in religious set- tings they are reduced to simplex relationships. Meeting together in other settings helps them to learn to care for one another.

Ministry to Migrant People

City people migrate. Some estimate ,that in North America people move to new locations an average of once in five years. This means that the urban church can count on losing 20 per- cent of its members each year! How can the church survive with such turnover?

It is clear that the urban church must absorb people rapidly into the life of

the church. They need to be incorporated into programs of worship and lay

ministry where their gifts are effectively used. Leadership, too, needs to be

flexible and creative. Prolonged Leadership apprenticeships and bureaucratic traditions built around

maintaining programs rather than ministering to people can kill the urban church.

The church must learn to minister to people at their own particular levels of spiritual development. In tribal and peasant churches, people spend their whole lives in the same congregation. An urban church has people for only a few years before they move on. Consequently, it cannot assume that it will help its members from their cradles to their graves. It must find out quickly where newcomers are in their spiritual maturity and build on that. Some are new believers in need of basic indoctrination and sup- port. Others are mature saints who need discussions of deeper spiritual matters. Still others may be experiencing stagnation in their faith. The urban church must help them to grow and it has little time to do this.

Finally, the city church must reach out to newcomers to its area. People are most open to religious change when they move to new settings. Nominal Christians, having lost their old ties, are in danger of dropping out of the church. Secular people may be looking for a meaningful community. The urban church must make special effort to find and contact those who move into its area.

Ministry to Immigrant Communities

People who immigrate to the city from tribal and peasant societies often build small ethnic enclaves that serve as halfway houses between their old ways and urban life. To reach such people, we must use the methods of tribal and peasant evangelism, namely, living among the people and building trust. Here the gospel often follows kinship lines and decisions are made after discussions with others in the community.

But urban immigrant communities are in transition. Their children and grandchildren are city folk. As we have seen, this leads to tremendous intergenerational stress, tensions that may be brought into immigrant churches. Mark Mullins points out (1987, 322-23) that churches made up of first-generation immigrants are ethnically conservative, but that "the history of immigrant churches reveals that the tendency toward conformity is ultimately the dominant force shaping their character. The process of assimilation forces the churches to choose between accommodation and extinction."

In the long run, churches that remain tied to ethnicity die out. By the third and fourth generations, ethnic churches in the city must de-ethnicize their identity and open the doors to outsiders if they want to survive. M. J. Yinger notes (1970, 112), "What will give one generation a sense of unifying tradition may alienate parts of another generation who have been subjected to different social and cultural influences."

First -generation immigrants want to hold services in their native tongue and style. For them the church is a haven where they can preserve the old ways with which they are comfortable. They choose pastors who reinforce their ethnic distinctiveness. Often such pastors are entrenched in their old ways and do not under- stand the next generation in their church. They are part of the problem, not of the solution to ethnic assimilation. When challenged by young elders to adopt new ideas and customs, they often resort to dictatorial ways to defend their positions.

Second-generation urban immigrants struggle with problems of language and cultural identity. At home their parents maintain old ways. In public they learn the new. The result is a breakdown of relationships between parents and children and an identification of Christianity with old ethnic ways that drives the young from the church.

It is critical that immigrant churches understand the forces of assimilation into city life or they will lose their children. They need to minister to the first generation with its anxieties about urban life. They need to minister equally to the second and third generations that are trying to find their way in the city. This requires leaders who are able to bridge the generations and pro- vide the people with hope. It requires bilingual or separate language services and pastoral ministries that help the old under- stand the young and the young understand the old. Above all it requires a vision of a new life that draws on both old and new and gives the people a strong sense of their own identity as Christians in the city.

Ministry to Foreign Enclaves

The movement of people is not only to the city and in the city, it is global. Cities today have enclaves of people from other lands. Some are immigrant communities. Others are businessmen, diplomats, students, and tourists whose stay is temporary. The modern city is not an autonomous community, it belongs to a global net- work of systems and relationships.

To evangelize the world today, we can begin by reaching out to the foreigners in our own cities. Many of the top leaders around the world have received training in other countries. Urban churches in these countries can reach out to international students in the universities near them, and top Christian businessmen can share Christ with their associates around the world.

Network Evangelism

As we have seen, networks provide one of the major forms of

social organization on the middle level of the city. People link up with other people through word of mouth, references, meetings, phones, faxes, and computers.

Ray Bakke (1984, 86) points to three kinds of networks: those based on kinship, on geography, and on vocation. To these we can add networks based on common interest and shared information. Each of these can serve as a means of evangelistic outreach.

Unfortunately, in an effort to build community or out of fear of

the world around them, many churches encourage their members to form their friendships only inside the congregation. Soon then the church members have few networks they can use to witness to the lost. Urban churches must encourage their members to form friendships with non-Christians. Moreover, Christians must make these friends feel at home when the latter visit the Christians' homes. If Christians are offended when such friends smoke in their homes or use off-color language, they will destroy the bridge of communication between them.

How can networks be used in reaching the city? We will explore a few of the many ways that networks can serve the church.

Home Fellowship Groups

One way to mobilize networks is through home fellowship

groups. The membership of the church is divided into groups of three or four families. Once a month these families meet in one of their homes and invite non-Christian friends for an evening of fun and fellowship. The evening is spent playing games, visiting, and possibly going to a restaurant or theater.

The object of these gatherings is not evangelism, but if occasions arise, members are encouraged to answer questions and wit- ness openly to their faith. These are opportunities for neighbors and friends to window shop Christianity and to see that it is not strange or cultish but genuine and compassionate. Preferably, the majority of those who attend should be non-Christians, so that they do not feel they are the target of high-pressure salesmanship. Through such gatherings friendships are built that, in time, may lead people to faith.

Linking Church Members to Evangelistic Teams

A second way to mobilize networks for outreach is to link people in the church to members of an outreach team. Elmo Warkentine, a successful urban church planter, points out that the old motto of "each one reach one" rarely works in a local congregation. Most Christians do not know how to effectively lead people to Christ or are uncomfortable in doing so.

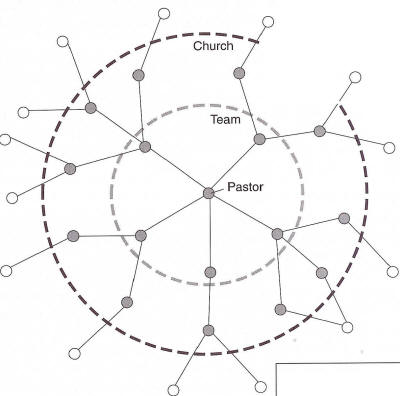

When planting new churches, Warkentine chose a few members with the gift and motivation for evangelism and trained them as an outreach team. He then linked everyone in the church to one of the members of this team. When the people came across opportunities for evangelism, they contacted their team member and he or she responded to the need (fig. 43, following page).

For example, imagine Mr. Jones, a solid member at church but unsure and inexperienced in evangelism. Through the church pro- gram he is linked to Mrs. Thomas, who is an excellent personal evangelist. One day Mr. Jones's neighbor, Mr. Peterson, dies. Over the next weeks Mr. Jones goes over to offer sympathy and help to Mrs. Peterson. He knows that Christ could help her in her sorrow, but feels uneasy about sharing the gospel with her in this time of her need. For one thing, he does not want to exploit her when she is vulnerable. For another, he does not want to break fellowship with her. If he points her to the gospel and she rejects it, their relationship is estranged. What should he do?

In Warkentine's program Mr. Jones helps Mrs. Peterson however he can and in the process tells her that he knows a woman who can help those going through times of grief. Mrs. Peterson can reject his offer without straining their relationship, because she is not rejecting him as a person. If she accepts his offer, Mr.

Figure 43 Evangelism by Network Referrals

Key

network of

relationships

church members

- - -

evangelistic team

- - -

Christians O

Non-Christians

0

Jones contacts Mrs. Thomas immediately and in a day or two she calls Mrs. Peterson to arrange a visit. She comes because she has been invited through the trust Mrs. Peterson has in Mr. Jones. Mrs. Thomas is, therefore, welcome. She can share about Christ with Mrs. Peterson and Mrs. Peterson can accept or reject the invitation without threatening her relationship with Mr. Jones.

Church members have many occasions when they can recommend help to friends and neighbors. People need help when illnesses, deaths, family conflicts, divorces, loss of jobs,

and

other crises strike and the church needs to be there to offer them assistance. Some churches have accountants, counselors, electricians, and mechanics who volunteer their time to help those who request their services and share their faith in the context of their aid.

Warkentine's approach has a second step to it. If Mr. Jones is willing to go

with Mrs. Thomas to visit Mrs. Peterson, he sees ministry modeled. After a few such occasions, he, too, may become interested in joining the outreach team. He then is discipled and assigned people who refer others to him for help. It is important not only to reach people in the world but also to multiply those who are involved in personal evangelism.

Special Interest Groups

A third way to use networks in the church is to organize special interest groups that nurture Christians in their particular walks of life and bring others to faith and spiritual maturity. An example of this is Christian business associations. Christians in the market- place gather in a neutral space and invite their non-Christian friends. The services are generally built on issues that interest people in the business world. Because of their common business experiences, these Christians are better able to share Christ with their non-Christian associates than are Christians in other specialized fields. Similarly, Christian doctors, nurses, academicians, politicians, construction workers, and other specialists can and do reach out to those in their vocations.

Special interest groups go beyond vocational associations. Single parents, young singles, old people, parents whose children are on drugs, women whose husbands are abusive or drunkards-all these need Christian friends who understand and help them through their particular trials. Churches need to be sensitive to their special needs, and stand by them with love and friendship.

One group has been particularly responsive in cities around the world, namely, students. Students are exploring new ideas and so are often more open to hearing the gospel than when they become established in their cultures and careers. Student ministries in high schools and universities have not only won many to Christ but also produced many strong leaders for the church.

Starting New Churches

One effective method of outreach has been to mobilize churches to start new congregations in new areas. In the New Testament, the church in Jerusalem grew into a megachurch. Some estimate it had more than ten thousand members. The Antioch church, by contrast, reached out by starting new churches and became the center of God's outreach (Acts 13).

One important reason for churches to plant new churches is that the city is so large that one church cannot minister to the needs of everyone. In hamlets and villages one or two congregations are enough to serve the community and everyone knows who is a Christian and who is not. In the city, a great many congregations are needed to reach all the people.

Another reason is the diversity of modern cities. City churches tend to serve

their own kind of people. Who reaches out to groups of people who have no

churches? Unless the church intentionally plants new congregations among

unreached groups and neighborhoods, they will not hear the gospel.

A third reason for planting new churches is the rapid growth of cities. Local churches look at their own areas. No one looks at the city as a whole. The result is a great neglect of entire areas of the city. Whole shanty towns and suburbs rise with not a church in them-and the surrounding churches are totally unaware of this. Discipling the whole city requires that somebody, whether denominational leaders or coalitions of churches, examine the city as a whole to find where congregations are most urgently needed and work toward establishing congregations in these areas.

Carrying Out Relevant Research

Planting new churches, whether through outreach by mother churches or by teams

of urban missionaries, must begin with careful research. If we do not study the city and the area where we plan to work, we will be blind to many of the social and cultural forces that can help or hinder our work.

First, we need to gather demographic data on populations, ethnic communities, class differences, and so on. Cities require extensive planning and the information gathered by government offices and businesses is available through libraries, city planning offices, police agencies, schools, hospitals, and business bureaus. Data

on

religious affiliation are available through city and national censuses. There is no need for the church to duplicate what the world already has done.

A second step is to select an area for ministry and to study it in depth. This requires ethnographic research methods. If a mother church is planting the new church, it is important that the elders and laity be involved in this research to sensitize them to the needs and opportunities of this new ministry. Using the existing church as the base, they should organize and train research teams; survey neighborhoods to determine ministry needs; visit the neighbor- hood to distribute tracts, visit people, show films, and become known and trusted by the local residents; start Bible studies; gather and instruct new believers; and form the new congregation in a home, school, or public building.

It is important not to separate research from ministry. If we think of first doing research and then ministering, we will either become mired down in research and never move on to ministry, or we will stop doing research and lose touch with the people. Research itself opens doors to ministry and ministry raises further questions that requires more research. A second danger is to confuse our own methodology with the work of the Holy Spirit. God has given the important work of evangelism to us and expects us to do it diligently

and intelligently. We must not, however, imagine that a perfect technique can be found that will coerce others to believe, or in any way replace the work of the Spirit in converting them.

A third step in research is to examine our own preconceptions as individuals and as churches about people and the work. Our deepest attitudes, hidden to ourselves but clear to the people we serve, are often the greatest barriers to effective outreach in the city. Frank discussions of our own prejudices against city life and other kinds of people is essential if we want to truly learn to love and minister to them.

Gathering People Together

After preliminary research, steps are taken to gather a group to form the

nucleus of a congregation. Sometimes a team is sent to hold tent meetings and

show Christian films for a week or more. A follow-up team then disciples the new

converts and organizes them into a Bible study and fellowship group. The team

must continue to assist the new congregation until it has its own identity and Leadership.

A second, probably more effective, method is for a church to intentionally divide and send a nucleus of its members to start a new congregation elsewhere. The mother church assists the daughter

church with finances until it is strong enough to stand on its own. Sometimes a

mother church organizes a number of preaching points and sends its members to help organize a new work.

In most of the world there are not enough seminary graduates to plant and pastor new congregations. Consequently, it is important

to disciple and empower the natural leaders that emerge in any human group. As a

young congregation grows, there will always be some members who arise as leaders

in the group. Properly discipled, they often become good pastors for the new church. This method has been effectively used by the Pentecostals in their rapid growth in Latin America.

These methods are effective in starting new churches among people of the same ethnic and cultural communities as the mother church. Planting churches in other ethnic and class communities calls for another approach. One way is to find a few Christians in those communities and to support them as they plant churches among their own people. This has been particularly successful in starting ethnic churches in the cities of North America. For example, parent churches find and help Vietnamese, Laotian, Hispanic, and Indian Christians to gather and organize churches. They assist the young congregations and often let these use their facilities.

Unfortunately, parent churches often take a paternalistic approach to the young churches, assigning them odd hours for services and making strict rules for the use of the sanctuary. It is hard for established churches to truly accept young congregations as full and equal partners, particularly when the former contribute most of the finances for church upkeep. Parent churches do not realize that the young congregations contribute much to the spiritual and social life of the church and that they, as old established Christians, have much to learn from the life and vitality of new converts.

These methods can help us plant churches where Christians exist. But many, if not most, people in cities around the world live in communities where there are no churches or Christians. To

reach these we must send cross-cultural urban missionaries who are willing to live in non-Christian communities, build trust with people, and share the gospel in culturally appropriate ways. This is an area in which we need much study. We know more about planting churches in tribal and peasant societies than we do about reaching urban communities in other cultures.

One thing is clear: there is a strong and growing resistance to Christian missions in many cities, particularly those in which Islam and Hinduism are dominant. Muslim and Hindu fundamentalist movements, centered in cities, are systematically organizing opposition to urban Christian missionaries and seeking to win Christian converts back to their old faiths. The battle to win the cities for Christ will not be an easy or a bloodless one.

Using the Media

In small communities, basic information is communicated by word of mouth. In cities, people depend on the media for general knowledge. Newspapers, magazines, books, billboards, radio, television, and computers flood the city with news, commentary, advertisements, sermons, music, and talk. To inform the city about Christ, the church must make effective use of the media available to it.

One effective method for reaching people is campaigns. Evangelistic crusades and mass rallies reach many who otherwise would never hear the gospel. But such campaigns often serve more as pre-evangelism than as effective evangelism. People hear the gospel and respond personally to the invitation, but many of them are never incorporated into the ongoing life of a community of faith. Consequently, their commitment dies through lack of nourishment. It is essential, therefore, that there be a systematic, long- term follow-up of the new converts to help them join living churches and grow in faith.

Another use of media is correspondence courses. This has been particularly effective in countries such as India and Africa where literacy is rising rapidly. Advertisements in newspapers invite people to write in for Bible study courses. The response is often overwhelming. Through well-designed courses, people are led to faith and to Christian knowledge. Many of them, however, do not join a church that can help them grow in faith.

Films, radio, and television, too, are powerful media that the church can use. In countries with open communication systems, these serve two major functions. They provide people with an

awareness of the gospel. This is particularly true when Christian programs designed specifically to reach non-Christians are broad- cast on secular stations. They also nourish Christians in faith. This is true particularly of Christian broadcasting stations. In countries where the government opposes Christianity and controls the media, radio and television broadcasts from other parts of the world in the languages of these countries do have an important role in spreading the' gospel.

Often we overlook mail as a means of letting people know about the church. Letters to visitors let them know that the church is interested in them. General mailings to a neighborhood keep people aware of church programs.

The phone, too, is a means of reaching the general public. Chinese churches in North America call people in the directory with Chinese names and let them know about Chinese gatherings. Some church planters use mass calling to invite people to the first ser- vices of a new church. A number attend and some join and form the core of a new congregation.

There are many other ways Christians have used media to plant and nurture the church. Billboards, newspaper advertisements, posters, cassettes, and videos have been tried with varying degrees of success, depending in part on the culture in which they are used.

Despite their power, modern media will never be the primary means of leading people to faith and to growth in Christian maturity in a congregation. These critical steps are most often taken through personal witness and invitation to fellowship in the church. Ervin Hastey writes,

New believers and new churches must be nurtured to Christian maturity if they are to reproduce themselves. Seed sowing and church planting without confirmation and follow-up stands no chance of impacting today's cities with the gospel of Christ. Strong churches grounded in biblical doctrine, energized by the Holy Spirit and filled with evangelistic zeal are needed today in our urban centers. (1984, 158-59)

Wholistic Ministries

The church in the first century proclaimed the divine message in public, taught from house to house and in public places, gossiped the gospel through informal witness, ministered to the sick, demonstrated the transforming power of the gospel in the lives of the people, formed fellowships of believers that showed the world a new kind of community based on love for one another, performed miracles, and cared for the poor.

The medieval church in the city saw itself as the refuge for the poor and needy. Protestant churches gave birth to the first public hospitals, schools, and orphanages. Only in the last century, with the emergence of the modern welfare state, have people looked to government as the body responsible for the well-being of everyone, including their education, medical care, retirement benefits, and welfare. This is particularly true in the west with its elaborate public programs administered by the government.

Today the church in the city must proclaim and live the whole gospel. It cannot relegate concerns for everyday human needs to the government and expect to be relevant to people. It must pro- vide for the care and nurture of its members, help feed the poor, heal the sick, counsel the distraught, care for the widows and orphans, and preach the Word with boldness. It must avoid the mental dichotomy that separates evangelism from social ministries and see both as ways to bear witness to the transforming power of the gospel.

Theological Issues in Urban Societies

Urban churches have great opportunities. They also face great challenges that vary greatly from one city to another. In many cities in the Third World, Christians often constitute a small, powerless minority in hostile settings. Moreover, they face incredible poverty and oppression. Churches in the west face other challenges, many of which spring out of modernity and its fruit. We can look here at only a few of the issues urban churches must deal with in doing their theology and ministry.

Building Community

The city is a place of alienation. People meet more and more people but they feel less and less a part of intimate communities. How can churches provide a sense of community in the midst of the depersonalizing systems of the city?

There were numerous kinds of clubs and institutions in the Greco-Roman society that the first Christians could have emulated. Rather, the New Testament writers chose the term ekklesia to describe the church. An ekklesia was not a voluntary association or a corporation. Its members were seen as children in the same family (Eph. 5:23; Acts 11:29), parts of the same body (Rom. 12:4-5; 1 Cor. 12:12), and citizens of the same colony (Phil. 3:20). In other words, the church was a true community that was more than the sum of its members.

The early church was a new kind of society characterized by agape and koinonia. Above all, however, it was a community with Christ in its midst. Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon write,

Christian community. . . is not primarily about togetherness. It is about the way of Jesus Christ with those whom he calls to himself. It is about disciplining our wants and needs in congruence with a true story, which gives us the resources to lead truthful lives. In living out the story together, togetherness happens, but only as a by-product of the main project of trying to be faithful to Jesus. (1989,78)

The church is always in danger of borrowing from the social models around it to organize itself. In so doing, it risks losing its distinct character as the body of Christ.

The Church as Crowd or Club

Churches in the city are in danger of becoming religious clubs. As we saw in the last chapter, clubs are single-purpose gatherings that people join on the basis of self-interest. Relationships in them are easily broken and members leave to join other clubs.

When a church organizes itself using the social principles of a club, it soon

becomes a club, no matter how much it preaches community. It is a group of people who gather only to fill personal

needs to worship God or experience fellowship. People join because of what the association can do for them, not because they are contributing to Christ's kingdom. They do not want the church to meddle in their private lives or to be asked to sacrifice their own interests for the sake of others.

Club-style congregations tend to be homogeneous, held together by the same ethnicity and social class. Members must constantly reaffirm the beliefs and practices of the congregation to show that they are in good standing and hide their disagreements for fear of ostracism. Open differences between members often lead to splits in the church because participation in the church is voluntary.

Club-style churches are not true communities in the biblical sense of the term. Their underlying assumptions prevent them from creating the new life of koinonia as a reality.

The Church as Corporation

The second dominant form of social organization in the city is the corporation. This is an institution with a formal organization, specialized professional roles, and bureaucratic management.

Large urban churches often take the shape of a corporation. They have formally

organized management with specialized paid professionals. Relationships are

based on contract. For those hired by the church, the contracts are formal and

can be legally enforced. Promotions and rewards are based on performance and

achievement. For the laity contracts are informal. Voluntary service is

encouraged but is generally seen as having less value than paid ministries. The

laity is the audience or the consumer. There is little participation in what

goes on on stage and little personal commitment other than paying to keep the church going. The church is run by specialists.

The primary services offered by many corporate-style churches is entertainment. Regarding televised services, Neil Postman writes,

Religion, like everything else, is presented, quite simply and without apology, as an entertainment. Everything that makes religion an historic, profound and sacred human activity is stripped away; there is no ritual, no dogma, no tradition, no theology, and above all, no sense of spiritual transcendence. On these shows, the

preacher is tops. God comes in as second. . . .

(1985,116-17)

Like businesses, this style of church is concerned primarily with what it "has to sell" the public and "how to make it attractive" to the people. It is concerned with planning and building programs, achieving quantitatively measurable goals such as attendance and contributions, increasing efficiency, and managing by objectives. As Peter Berger (1973) and Jacque Ellul (1964) point out, in such cases the concern with technique dominates church life.

As Guinness (1993) points out the great dangers megachurches face as they seek to bear witness to the gospel while adopting many of the trap- pings of modernity.

Church as Covenant Community

How can the church truly remain the body of Christ in the midst of the urban pressures to reduce everything to economic models and associations based on self-interest?

Clearly the church must avoid acting like a club or a corporation. Rather it

must provide a radical alternative-a covenant community in which Christ is the head and the desires of the members are second to the building of the kingdom of God. In one sense the church is a community like other human communities, a living reality fleshed out in the concrete human relationships and experiences of life. In another sense, it is unique because it is a gathering in which God is present and at work (Phil. 1:1-11).

Membership in the church as community is not optional for a Christian. Nor is it based on contracts with the church as a corporate body. It is based on a person's relationship to Jesus Christ. Everyone who is Christ's follower is a member of the church. No one can exclude such a follower from the church on the basis of class, ethnicity, culture, or gender.

The church ultimately does not exist for the well-being of its members. C. Norman Kraus writes, "[The goal of Christianity is not] the self-sufficient individual secure in his victory through Christ enjoying his own private experience of spiritual gifts and emotional satisfaction" (1974, 56). It exists to glorify and obey its Lord. Hauwerwas and Willimon write, "[The church is] a place, clearly visible to the world, in which people are faithful to their promises, love their enemies, tell the truth, honor the poor, suffer for righteousness, and thereby testify to the amazing community - creating power of God" (1989, 46). The church also exists

as

God's prophetic voice calling the world to repentance, salvation, and reconciliation.

Because they follow the same Lord, members of the church are committed to each other. The inner bond and essence of life that holds them together is love-the commitment of each member to "be for" the others in self-giving service. This love transcends all social, economic, gender, and racial distinctions that divide human societies (Gal. 3:26-28; Col. 3:10-11). The result is a new family, a new race, a gathering of those who share the same Lord and Spirit and who devote themselves to one another's well-being (Acts 2:42-34). In such a community, members cannot leave when they are dissatisfied. They must learn to live together in harmony, to sacrifice their personal interests for the sake of the body, and to respond to the call of their Master.

Life in the community church is multidimensional. There is no division between spiritual, social, and economic needs. Members minister to one another as whole persons. Moreover, this reciprocity

is not based on a quid pro quo. Members contribute according to their gifts and receive according to their needs. There is no calculation of an equality of exchange.

Is it possible for local churches to truly be covenant communities in an urban setting? The early church was and it drew the lonely and lost into its fold. If the church today loses its battle against being a religious club or a corporation, it will be or it is in danger of becoming just another human organization captive to its times. If the church wants to reach the city, it must first be the church in the biblical sense of that term-a place where Christ is in the midst and the Holy Spirit is present in holiness and power.

Church Buildings

One major problem urban churches face is finding suitable facilities for worship

and ministry. The high cost of land and construction, particularly in inner-city areas, and the poverty of most Christians around the world make it impossible for them to build a large building and support a fully paid pastor.

One solution is to meet as house churches in the homes of the members. This has been an important solution, particularly in cities where Christians are not allowed to meet openly, such as in parts of China, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia.

House churches are also an answer in other cities, particularly in the early

stages of organizing a new congregation. The problem is that house churches tend

to be transient. One study of a number of denominations found "that families will not stay with the house church more than two years" (Maroney, Hill, and Finnell 1984, 127).

There are other solutions to the problem of buildings. Congregations in

Singapore have bought theaters and converted them into churches. In many cities

they buy or rent shops and have store-front churches. Increasingly, several

congregations from different language groups share the same building. Despite these creative

alternatives, church buildings remain a major problem in cities around the

world, and parent churches and missions involved in urban church planting must

generally help new congregations find and finance places to meet.

The issue of buildings goes beyond places to meet. In cities, buildings are powerful symbols. It is significant that the tallest and most impressive buildings in most cities are owned by banks, businesses, and insurance companies. Large churches with prominent buildings are public signs of the presence of Christ in the city. However, we do need to be aware of the message they convey. Most appeal to upper- and middle-class people. Some speak of the gospel as an import from the west. We need indigenous but clearly Christian architecture.

Ethnicity and Linguistic Diversity

Ethnicity is a strong force, both in uniting people from the same language and culture and in dividing them from others. What is the proper place of ethnicity in the church?

The sociocultural realities are that people belong to different communities and that they like to associate best with their own kind of people. It is natural for people to wish to associate with others who think, talk, and act in familiar ways. Consequently, they are most easily evangelized by building different churches for each sociocultural group.

But no church can keep people out for not being of the "right" ethnic group. The Bible is clear that the followers of Christ belong to a new people that takes priority over their old worldly identities. If Christians do not learn to live and express their unity, the

church will become a part of the world's structures that perpetuate poverty, divisions, hostilities, and wars. Christian growth means that we must challenge our existing sociocultural systems, what the Bible calls cosmos (world) and SQTX (flesh), and be trans- formed into God's new order.

The urban church may begin by evangelizing different ethnic and class groups, but it must also build bridges of reconciliation and love between them. In many cities, the church is the only body that can bring reconciliation between hostile gangs and ethnic communities.

Reconciliation often begins first with the leaders and pastors, but it must spread to the congregations. Paul writes that the fact that rich and poor, Jew and Gentile, males and females worship together in love and harmony is itself the sign of God's trans- forming power on earth.

Finally, we must help Christians to mature to the point where they see that

their primary identity is Christian, not upper-class, or white, or male. When we

truly realize that a Hispanic or an African-American or an Egyptian Christian

man or woman is closer to us than our biological brothers and sisters who are

not Christians, then we can celebrate our diversities because we know that underneath we are truly one. If, however, our earthly distinctives are our most fundamental identities, we know that no matter how much we enjoy each other's company, we will stand divided when things go wrong.

Poverty and Shattered Dreams

The city is a place of dreams. It attracts the rura1 poor, the refugees, and the young seeking a better life,

and many who come to the city do find a better life. But the city is also a

place of shattered dreams. Between one-half and two-thirds of the populations of many cities in the developing world live in slums and squatter settlements. Over three-fourths of the population of Calcutta live in overcrowded housing, with 57 percent of the families living in one room and an estimated one million living on the streets (DuBose 19S4a, 55). What is the church's responsibility to these multitudes of urban poor? Clearly, God loves all people, including those who are poor.

The early church saw ministry to the poor as an essential part of its mission. Paul took up an offering for needy Christians in Jerusalem. The medieval urban monastic orders, led by Francis of Assisi, ministered to the destitute. The evangelical church of the nineteenth century began hospitals, schools, orphanages, and homes for the needy. It was the church, not the state, that first took care of those adrift on the margins of society.

America has long had a church of the urban poor. This is seen in the many store-front churches, inner-city missions, and industrial missions. It is also seen in the vital African-American church that has emerged in the cities since World War II. But the urban poor have been marginal to the central stream of American Protestantism, both mainline and evangelical.

For the most part, Protestant churches have failed in their mission to the poor. Viv Grigg (1992) gives a number of reasons for this. One of these is our failure to really see poor people around us. We keep away from the areas of our cities where the needs are greatest. Another is our belief that if economic growth takes place in the city, the poor will rise. With this goes the myth that the poor can improve their condition if only they work harder. Most poor people do work hard and little of any economic expansion trickles down to them.

A third reason Grigg gives for the failure of the North American church to reach the urban poor is spiritual. "A church trapped by cultural perspectives on affluence rather than adopting the biblical stance of opposition to the 'god of mammon' has exported this into missions." In missions we stress identifying with people culturally, but we have not been willing to identify with people in their poverty.

In most cities of the Third World the church is mostly poor. In this sense, we are coming full circle to the apostolic era when most churches and Christians were poor (DuBose 1984a, 70).

Toward a Theology of the Urban Poor

Before the church can effectively minister to the urban poor, it must develop a theological foundation for such ministries. In a word study of the Old Testament, Thomas Hanks concludes: "Oppression is viewed as the basic cause of poverty (164 texts). In the case of the other 15 to 20 causes for poverty indicated in

the Old Testament the linguistic link is much less frequent-not more than 20 times" (Grigg 1992, 89). The writers of Scripture do not blame people who are poor for their poverty or see them as inferior and lazy. Rather, they are people whom God loves in a particular way because they have been crushed (Deut. 24:14, 19-22; James 2:1-7; 5:1-6).

A theology of the poor must begin with Christ. His incarnation among the poor, his miracles, and his suffering model for us what our ministries should look like.

This theology must also proclaim the kingdom of God that has invaded the cities of the earth wherever God's people gather to worship him and live together in peace and reconciliation. The kingdom outlines the scope for our ministry, which should include preaching the good news of salvation, healing the sick, feeding the hungry, educating the ignorant, and seeking to trans- form the structures of society that oppress people and keep them poor (Luke 4:18-19).

The kingdom also determines our attitudes in ministry. We must not serve people who are poor from positions or attitudes of pride and superiority. If we do so, we only add to their oppression. We must be aware that we, too, are sinners and paupers. It is only the grace of God that has transformed us, and we did not deserve that grace any more than others. Nor can we ourselves save the poor. It is God who must do so. We can only share what we have experienced of his deliverance. We must come as paupers, pointing people

to God, who can transform their lives. We must join as brothers and sisters those who follow Christ. We need to realize that we have more to learn from people who are poor about faith and dependence on God than we have to offer them by way of material aid.

Ministry among the Poor

Our goal in ministry is not simply to help poor people to meet their daily needs, but to see them transformed by the power of God and empowered to be people of dignity and worth in society. We may need to begin with food, clothing, and shelter, but we must move on to the transformation of people and social structures. If we do not, our ministry can exacerbate the cycle of poverty.

There is no single way to minister among the poor. They are widely diverse in their needs, cultures, and abilities to help themselves. Our ministry must begin by learning to know people and identifying ourselves with them. Then, in partnership with them, answers can be sought to meet their needs. They must have the say in what needs to be done and how to do it, or we keep them powerless and dependent.

How can a church help? In part, the answer depends on the social position of the church. The ministry of affluent churches outside the communities of the poor must be different from that of the churches of poor living in the midst of such communities.

Mobilizing affluent churches

In a sense, the problem of poverty is not so much a problem of the poor but of

the rich and powerful. Transformation must begin with a change in the attitudes

and actions of prosperous Christians and churches. They must reject the urban

environment's tendency to evaluate people by wealth and see, as the Bible does, the dignity and worth of every human being. They must see them- selves as members of the same body with their poor sisters and brothers in faith. They must know deep within themselves that sharing is greater than accumulation of wealth and that the well being of others is as important as their own.

How can well-to-do churches serve the poor? Some middle- class churches have

felt the particular burden to begin ministries to help feed, educate, and

befriend the needy. Downtown churches in increasing numbers open their doors in

winter to provide temporary lodging for the homeless. Church agencies have engaged in economic and community development projects.

But the church must go beyond relief and development. It must call people to be transformed by the gospel. Only as people themselves are changed will there be a change in their conditions.

The church must also work to transform the social structures that keep the poor poor. It can begin by establishing cooperatives and lending associations that free poor people from the high prices of shopkeepers who come from outside and from the usurious interest rates of money lenders. It can help squatters to get legal titles to the land on which they live and mediate between them and the police whom they distrust. It can speak out publicly for the rights and dignity of poor people and lobby the government to provide them with water, sewers, and roads. It can work to change structures that oppress.

Roger Greenway points out that there are particular obstacles to helping the homeless (1989, 187). Many of them are transient and live isolated lifestyles. They mark out little circles of space where they guard their meager possessions and are resentful of outsiders who approach them.

Another obstacle is recidivism. Individuals come off the streets, or out of jail, only to "run" after a time of success. The entreaties of old friends and drug pushers and the freedom of street life are appealing when pressures rise. The marginalized live with a sense of failure, and those who minister among them must be willing to live with frustration and disappointment.

Ministry among the homeless cannot be done out of duty. It must be born out of love for people. If we come as saviors to those in need, we provide immediate help, but in the long run we only add to their despair. We need to look them in the eyes and see not their sin and squalor. We must see them as God sees them, created in his image, redeemable and potential saints in eternity. Above all else, we must remember our own broken, sinful state and the redemption we ourselves have found in Christ. Only then will we be willing to share with them as brothers and sisters and not as paternalistic philanthropists.

Our love must be unconditional. Certainly we want people to receive the Good News and become Christians, but we should not use ministry to manipulate people. We must love them even if they reject Christ, just as God continues to love us even when we sin.

Identifying with the poor

Ministry by affluent churches in poor communities is essential, both for the well-being of the poor and the spiritual vitality of the rich. But this is not enough. There need to be teams of Christians who are willing to live and plant churches among the poor. In the Middle Ages, preaching friars and monks planted churches among the poor in the cities of Europe. In more recent years Roman Catholic orders have ministered among the poor and helped them establish base communities. Protestants, too, have begun work in the slums and squatter settlements of the world's great cities (Grigg 1992). The great Japanese Christian Toyohiko Kagawa went to live in the slums of Tokyo and Agnus Lieu serves in the sweatshops of Hong Kong.

It is important that missionaries to the poor go in teams. In many ways missionaries raised in affluent lifestyles find it harder to adjust to living with the poor in their own society than with tribal and peasant people abroad. The shock is even greater when they identify with the poor in Calcutta, Lima, Manila, or other cities where massive poverty exists.

Because the demands on the family are so great in such ministries, some, such as Grigg, recommend that the teams be made up of single people and young couples who delay having children for the sake of ministry. In any case, fully incarnational ministries to people living in poverty are needed.

Church movements among the poor

Church planting teams are not the end of the story. Today churches among the poor are beginning to plant other churches. In Latin America, in particular, poor churches, many of them charismatic, are reaching out to their neighbors and establishing new congregations.

Local leaders are essential to such movements. These churches cannot wait for leaders who have finished formal theological education. Moreover, such education often alienates students from poor communities. The most effective leaders are those who emerge in the context of everyday life and have vision, zeal, and the gifts of organizing and guiding people. Most of them must earn their own living and minister out of their passion for Christ. They need Bible training, but can get it only through personal discipling, night courses, or ongoing seminars.

Many church movements among poor people have been accompanied by an emphasis on God's miracles. People look for visible demonstrations of God's transforming power. A wholistic

ministry does not consist of preaching the gospel and dispensing medicine in

separate contexts. This only reinforces the western dual- ism between spirit and

matter, evangelism and social concern. Ministry consists of preaching and

teaching, praying for the sick, providing medicine, sitting with people to

comfort them when they are bereaved, and celebrating with them when they are

healed in an integrated fashion. We need to demonstrate the power of prayer and

of God's extraordinary healing and provision. All healings are God's healings and are miraculous. Some seem more ordinary than other, but we must expect and affirm them all.

Poor people need dignity and hope. On a daily basis, they are despised by the

society in which they live. The sense of powerlessness breeds hopelessness and despair. The church must pro- vide people with a sense of their dignity and power as new creatures in Christ. With this comes hope, joy, and the ability to change conditions.

Finally, it is worth repeating that urban poor Christians have much to offer to

rich suburban Christians who have difficulty with spirituality because their

lives are too comfortable. Rich churches need to hear the prophetic voices of

their poor sisters and brothers, and learn again what it means to trust God in the happenings of everyday life.

Dealing with the Urban Worldview

The church must learn to live in the city and speak its language, but it must never sell its soul to the urban worldview. The gospel must be good news to those trapped by the alienation, hedonism, greed, oppression, and poverty of the city. It must challenge the values of the city that destroy people.

Extreme Individualism

The city nurtures individualism. The effects of this are both positive and negative.

On the one hand, the city frees people from the tyranny of small, ingrown communities and of traditions. Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists are more open to the gospel in urban settings. It is easier there for them to get away from the persecution of relatives and neighbors. (Weak Christians, however, often drop out of the church when they move to the city.)

On the other hand, the stress on individual freedom rather than on group responsibilities cuts people off from enduring relation- ships of kin and community and leaves people alienated in large impersonal institutions. The urban church must continually fight against this extreme individualism that tears down communities of support and accountability. It is hard for an urban church to preach against sin and to discipline its members if they have no loyalty to it and are willing to leave and join another church. The result is a weakening of morality not only in the city but also in the church.

The church must oppose the self-centeredness, materialistic narcissism, and hedonism that thrive in urban settings and are fostered by high mobility. It must also resist the tendency to turn worship into entertainment, fellowship into racism and class ism, and service into self-gratifying paternalism.

Human Engineering

The heart of public urban structures is a mechanical view of order (Berger et al. 1973; Ellul 1964; Guinness 1993). The city is the product of human engineering and engineering presupposes that the world is determined by predictable laws of cause and effect. This is what makes planning and human control possible. Rural people are aware of rains,

droughts, plagues, seasons, and other forces beyond their control. City people

turn night into day, winter into spring, and bring faraway places into their own

neighborhoods via the media. Through science and technology they control diseases, create amazing new products, and gather vast storehouses of knowledge. In such a worldview it is hard to see the place for God. The temptation for city folk is to be self-reliant- to think that with proper knowledge, planning, and effort they can achieve their goals by themselves.

This dependence on human engineering also spreads to the churches, especially upper- and middle-class urban churches. There, long sessions in prayer and waiting for the leading and power of the Holy Spirit are replaced by planning boards, goal set- ting, strategy sessions, and mobilization of the

people. The life of the church-becomes a program imposed from outside the Christian, not a vision and life that springs up from within.

Certainly there is a place for planning and human effort, but we must remember

that the growth and vitality of the church are not founded on human might,

power, planning, or management by objective. They are founded on the Spirit of

God. The church is Christ's body, not our human organization. Its life has his

life flowing through it, not mere enthusiasm generated by human programs. This tendency to human engineering is particularly strong in western cities with their modern worldview. They have much to learn from the powerless Christian minorities in cities around the world who have had to learn from experience that all that they have comes from God.

Pluralism

One set of problems urban churches face emerges out of the pluralism of the city. People of many different religions gather here. How can Christians affirm their faith, while working together in the same society with people of other faiths?

One solution is to make one religion dominant and to tolerate other religious

communities so long as they do not disturb the majority community or convert

others. This is the policy in cities where Muslim law is enforced. There,

Christians face a great deal of harassment and are often prohibited from having

church buildings. Above all, they are prohibited from evangelizing their neighbors, especially Muslims, on pain of harsh persecution. Many of these Christians have a strong faith forged by suffering.

Another solution is for a nation to declare itself a secular state and to let all people practice their religions so long as they do not violate the public rights and disturb the peace by upsetting people in other religious communities. The question then arises: what effects does this split between public and private spheres of life have on the country and on the church?

The first consequence of establishing a secular government is that morality in

the state is reduced to law. There is no sense of sin in the public sphere.

Christians must consequently struggle with the tension between the ethics of the

gospel and the commonly accepted practices of the society around them. It is

hard for the church to take a strong stand against premarital sex, greed, shady